|

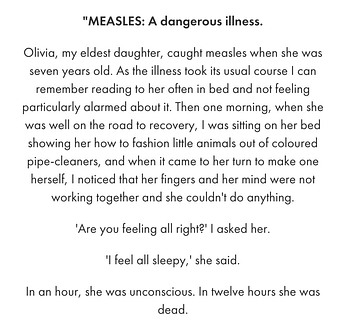

| New York Times chart, with CDC data, shows the risks of measles and the vaccine that prevents it. |

Your Local Epidemiologist

Yesterday I got a Google news alert: “Measles.” Yes, measles. In the 21st century. At the height of winter. Measles typically spreads in spring. What’s going on?

A measles case here or there is not abnormal. We see them every year. Cases typically come from international travelers, but sometimes locally acquired outbreaks emerge among unvaccinated pockets.

Cases today are still far, far, far below rates in the 1950s and ’60s thanks to vaccines. However, when we zoom into the past 10 years, we see a slow but steady rise. This shouldn’t be a surprise, given the reduction in routine vaccination coverage and the increase in vaccine exemptions.

Also, measles has epidemic cycles. It flares up every four to five years—2008, 2011, and 2019. It is exactly five years since the last flare-up, which suggests this may be a bad year. Of course, the pandemic could throw off patterns, but we aren’t off to a great start.

What is (and is not) a way forward?

Measles is preventable. And, in the Pennsylvania outbreak, one unvaccinated child went to daycare while infected, defying isolation.

People are disappointed and shocked that fellow parents wouldn’t vaccinate their children. People are angry that their loved ones may get exposed as a result, especially since babies under 12 months old cannot be vaccinated. I share a lot of the frustration. But I remember what Dr. Sandro Galea said during the pandemic, “We cannot finger-wag our way to a healthier world.”

As generations age, the memory of mid-20th-century diseases like measles fade. Measles is the most contagious disease, with an infected person infecting an average of 12 to 18 others (assuming no immunity in the population). In some cases, a single person has infected hundreds of people.

It’s not “just a fever or a rash.” While most people who get measles will recover, it can harm the body in every way possible. Measles can wipe out a huge fraction of immune memory to other diseases, causing an increase in all-cause deaths. The risks of infection far outweigh the risks of the vaccine.

One of the biggest challenges is the rise of individualism. It goes against public health’s DNA: a collective response for the good of the population. We desperately need to engage with people who find individualism increasingly important. Develop interventions with them.

Is this due to a recent and dramatic decline in trust? Let’s do something about it. Mistakes were made during the pandemic. Misinformation is supercharged by social media. Bad actors, like the disinformation dozen, drive the majority of anti-vax content. Politics are further dividing individual health. Many people talk about these challenges, but I’m getting increasingly frustrated with inaction.

Yesterday I got a Google news alert: “Measles.” Yes, measles. In the 21st century. At the height of winter. Measles typically spreads in spring. What’s going on?

- Two active and unrelated measles outbreaks among unvaccinated people: Philadelphia and New Jersey

- A Delaware children’s hospital on alert after an unvaccinated patient exposed 30 others

- Two D.C. airports on alert for an unvaccinated, infected international traveler

- An explosion of measles cases in the U.K. in the past month (255 cases)

A measles case here or there is not abnormal. We see them every year. Cases typically come from international travelers, but sometimes locally acquired outbreaks emerge among unvaccinated pockets.

Cases today are still far, far, far below rates in the 1950s and ’60s thanks to vaccines. However, when we zoom into the past 10 years, we see a slow but steady rise. This shouldn’t be a surprise, given the reduction in routine vaccination coverage and the increase in vaccine exemptions.

Also, measles has epidemic cycles. It flares up every four to five years—2008, 2011, and 2019. It is exactly five years since the last flare-up, which suggests this may be a bad year. Of course, the pandemic could throw off patterns, but we aren’t off to a great start.

What is (and is not) a way forward?

Measles is preventable. And, in the Pennsylvania outbreak, one unvaccinated child went to daycare while infected, defying isolation.

People are disappointed and shocked that fellow parents wouldn’t vaccinate their children. People are angry that their loved ones may get exposed as a result, especially since babies under 12 months old cannot be vaccinated. I share a lot of the frustration. But I remember what Dr. Sandro Galea said during the pandemic, “We cannot finger-wag our way to a healthier world.”

As generations age, the memory of mid-20th-century diseases like measles fade. Measles is the most contagious disease, with an infected person infecting an average of 12 to 18 others (assuming no immunity in the population). In some cases, a single person has infected hundreds of people.

It’s not “just a fever or a rash.” While most people who get measles will recover, it can harm the body in every way possible. Measles can wipe out a huge fraction of immune memory to other diseases, causing an increase in all-cause deaths. The risks of infection far outweigh the risks of the vaccine.

One of the biggest challenges is the rise of individualism. It goes against public health’s DNA: a collective response for the good of the population. We desperately need to engage with people who find individualism increasingly important. Develop interventions with them.

Is this due to a recent and dramatic decline in trust? Let’s do something about it. Mistakes were made during the pandemic. Misinformation is supercharged by social media. Bad actors, like the disinformation dozen, drive the majority of anti-vax content. Politics are further dividing individual health. Many people talk about these challenges, but I’m getting increasingly frustrated with inaction.

Bottom line: Unfortunately, measles is off to a great start in 2024. We expect trends to increase. We need to heed the underlying warning. A laissez-faire approach to public health, on both sides, will not work. Harrowing stories like Roald Dahl’s below will creep into the 21st century. We can do better.

A big thanks to Edward Nirenberg for his help pulling a lot of the research integrated above.

Your Local Epidemiologist is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H., Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including the CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public-health world so people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members.

Your Local Epidemiologist is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H., Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including the CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public-health world so people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members.

from KENTUCKY HEALTH NEWS https://ift.tt/PaL4qYe This looks like the year for an epidemic of measles, the most contagious disease, which can be deadly but is very preventableHealthy Care

0 Response to "This looks like the year for an epidemic of measles, the most contagious disease, which can be deadly but is very preventableHealthy Care"

Post a Comment